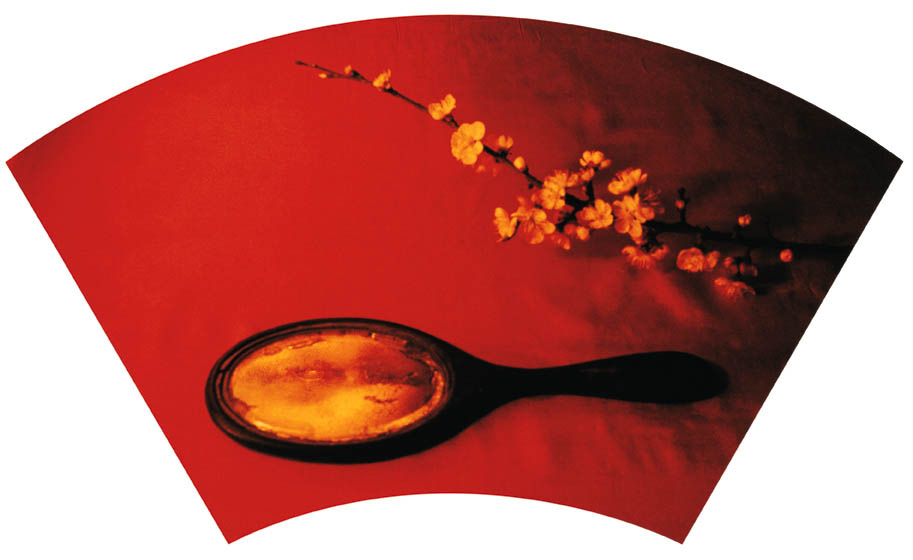

In Chen Lingyang's photographic series, Twelve Flower Months (1999-2000), we encounter an arresting juxtaposition: traditional Chinese flower arrangements reflected in mirrors that reveal the artist's menstruating body. This suite of images challenges us to ask:

How do we read the signs of the female body in art? What language can capture both the material reality of menstruation and its rich symbolic dimensions?

Traditional art criticism often separates these realms, treating bodily processes as either purely biological or abstractly symbolic. In my research, I've found this separation inadequate for understanding art that embraces women's embodied wisdom. This has led me to develop a new conceptual framework I call "Femiotics"—a critical lens for interpreting the signs and symbols of female embodiment in art, particularly those that disrupt boundaries through natural processes like menstruation.

The Birth of Femiotics

The concept of Femiotics developed from my research into how menstrual blood is visualised and made meaningful in contemporary art. While menstruation is increasingly referenced in popular culture, the art world has developed uniquely powerful visual languages for interpreting female embodiment that deserve their own analytical framework.

Femiotics (n.): A critical and artistic framework for interpreting the signs and symbols of female embodiment, particularly those that disrupt normative boundaries through leakiness, excess, and abjection, such as menstruation. Rooted in the confluence of semiotics and feminist phenomenology, Femiotics examines how the female body—materially and performatively—produces meaning in contemporary art, challenging patriarchal containment and celebrating formlessness and carnivalesque subversion.

At the heart of Femiotics is what Mary Jane Lupton calls 'gendered blood'—menstrual blood that has been culturally transformed into a loaded sign system. This blood struggles against patriarchal traditions that have long suppressed images of menstruation while simultaneously objectifying women's bodies for male viewing pleasure. Femiotics provides us with a kaleidoscopic methodology to decode these complex contradictions (which we will come to shortly).

Femiotics unfolds through three lenses to unpack these signs: material, focusing on physical properties like the sticky viscosity of menstrual blood or the creamy warmth of breastmilk; symbolic, exploring cultural meanings, such as blood’s abjection or milk’s tie to motherhood; and performative, examining public acts, like displaying blood or offering milk in a gallery. This triad—body, meaning, action—reveals how art transforms female embodiment into a feminist force, a kaleidoscope of vibrant, unruly patterns.

Traditional approaches to art criticism often prioritise the viewer's disembodied gaze—echoing Descartes' "I think, therefore I am." In contrast, Femiotics embraces Fluxus artist Shigeko Kubota's radical inversion:

"I bleed, therefore I am."

This framework provides an embodied understanding of how menstruation transforms women's experiences into lived, spatial realities that challenge patriarchal visual traditions. Artworks may contain one Femiotic, or many:

Femiotic (n.): A sign or symbol of female embodiment in art that disrupts normative boundaries through leakiness, excess, or abjection, such as menstrual blood, breastmilk, or a witch’s spell. Analyzed through the Femiotics framework, a Femiotic embodies material, symbolic, and performative dimensions—its physical form (e.g., blood’s viscosity), cultural meaning (e.g., milk’s taboo), and public enactment (e.g., casting spells)—challenging patriarchal containment and celebrating formlessness and subversion.

Femiotics isn't just about menstrual blood—it embraces breastmilk and witches, and other boundary-crossing signs. In Jess Dobkin's The Lactation Station (2006), breastmilk sipped in a gallery defies maternal norms with its leaky excess. Witches, with their potions, cauldrons, and pointy hats, emerge as potent femiotic signs of 'uncontrollable' female power. Their spellcraft—brewing unguents, casting hexes, flying beyond boundaries—mirrors the leaky body's materiality and refusal to be contained.

When artists like Remedios Varo, Betye Saar, or Kiki Smith invoke witch imagery, they tap into a rich tradition of female knowledge deliberately marginalised by patriarchal structures. The witch's carnivalesque traits—her formlessness, her boundary-crossing, her challenge to rational order—echo menstrual blood's disruptive potential. These signs—blood, milk, witch—broaden Femiotics, revealing art's power to transform stigmatised female embodiment into sources of creative and political resistance.

The Theoretical Landscape

Femiotics synthesises ten key theoretical frameworks while creating something distinctly new:

From Kristeva's concept of abjection, Femiotics recognises menstrual blood as that which "disturbs identity, system, and order by not respecting borders, positions, or rules." Menstrual blood is quintessentially abject as it crosses boundaries between inside and outside, clean and unclean. Yet artists working with menstruation don't simply exploit its shock value; they reconfigure its meaning, turning abjection into a site of power.

Creed's work on the monstrous-feminine informs how Femiotics interprets artworks that embrace rather than reject the supposedly "horrific" aspects of female biology. When artists like Judy Chicago or Ingrid Berthon-Moine boldly display menstrual blood, they challenge deep cultural anxieties about female bodily processes that have long been coded as monstrous.

From Grosz and Shildrick, Femiotics adopts a sophisticated understanding of the leaky body. Their work reveals how female bodies have been culturally constructed as problematically uncontained compared to the supposedly sealed male body. Femiotics reads artistic representations of menstruation as challenges to this construction, reclaiming leakiness as a source of creative power.

Young's ‘phenomenology of feminine embodiment’ provides Femiotics with tools to understand how menstruation is lived and experienced, not just observed. Her insights into women's hiding in the menstrual closet and the spatial politics of female embodiment help us understand why artistic revelations of menstruation are politically charged.

Femiotics employs Butler's theory of gendered performativity to analyse how menstrual art performs gender—either reiterating or subverting cultural norms through the visibility of blood. When artists make menstruation visible, they disrupt the performative concealment that Butler identifies as central to constructions of proper femininity.

Irigaray's concept of the female imaginary enriches Femiotics with its vision of a feminine symbolic order outside patriarchal constraints. Her famous notion of the "two lips speaking together"—(referring to the self-touching labia)—perfectly captures the auto-erotic self-sufficiency Femiotics identifies in menstrual art. Femiotics draws on her celebration of female fluidity as resistance against masculine solidity and containment, revealing how menstrual art often embodies this alternative feminine logic that refuses to be defined by patriarchal binaries.

Cixous's écriture féminine—writing the female body—offers Femiotics a way to understand menstrual art as a form of embodied inscription. Her call to "write your self, your body must be heard" finds visual expression when artists use menstrual blood as medium. For Cixous, women's corporeal writing disrupts the patriarchal symbolic order with its rhythms, excesses, and pleasures.

From Foucault's concept of heterotopia, Femiotics understands how menstruating bodies create 'other spaces' that challenge normal social orders. These spaces exist both physically and symbolically—in galleries displaying menstrual blood and in the cyclical experience of menstruation itself. Where patriarchal systems frame these cycles as 'crises' to be contained, Femiotics recognises them as sites of meaning-making.

Bataille's concept of the Informe (formlessness) provides Femiotics with a framework for understanding how menstrual art disrupts formal categories. For Bataille, the Informe operates as an operation that "serves to bring things down in the world," challenging classification systems and hierarchies. Menstrual blood in art performs this disruptive function—it refuses containment, challenges binary distinctions, and resists categorisation.

Finally, Bakhtin's carnivalesque informs how Femiotics interprets menstrual art's subversive potential. His concept of the 'classical body'—that idealised form where "all orifices are closed"—helps us understand why menstrual art is so disruptive. When artists showcase menstrual blood, they challenge visual traditions that privilege the contained body, transforming what was hidden into a carnivalesque celebration.

“Femiotics is a feminist kaleidoscope, revealing the vibrant patterns of women’s bodies in art.”

Reading Art Through a Femiotic Lens

Applying Femiotics to specific artworks demonstrates the framework's analytical power. Returning to Chen Lingyang's Twelve Flower Months, a Femiotic lens reveals how the artist creates multiple layers of signification: the flowers (traditional symbols of femininity and seasonality), the mirrors (spaces of visual doubling), and menstrual blood together form a complex semiotic system that challenges traditional representations of female cycles.

A 'network of gazes' emerges in Chen's work—when we view her mirrors reflecting her menstruating body, we participate in a complex visual exchange where we watch her watching herself, while her blood becomes both object and subject. This multilayered signification demonstrates how female bodily experiences create unique semiotic structures that traditional art criticism often misses.

Consider also Zanele Muholi's Isilumo siyaluma series (2011), where digitally manipulated menstrual blood stains form kaleidoscopic patterns on cotton rag. Through a Femiotic reading, these works speak to how menstruation functions as both a personal experience and a political statement. Muholi, as a Black lesbian artist from South Africa, uses menstrual blood to address intersecting systems of oppression, where the bleeding female body becomes a site for challenging not just gender norms but also racial and sexual prejudices.

Why Femiotics Matters

Femiotics matters because it recognises a significant cultural shift: menstrual blood has moved from the margins into the public realm of art. This movement isn't merely about increased visibility; it represents a fundamental challenge to dominant ideologies and prejudices. By naming and theorising this shift, we can better appreciate how these artistic expressions productively question gender essentialism.

By introducing Femiotics as a framework, I hope to contribute to what Foucault called "the intellectual destroyer of evidence and universalities"—a way of thinking that locates "weak points" in dominant systems and opens new possibilities. When we apply a Femiotic analysis to art featuring the leaky body, we don't just gain new interpretive tools; we participate in a broader cultural transformation that says women need no longer hide in what Iris Marion Young called "the menstrual closet." Femiotics gives us a language to celebrate rather than shame these fundamental human processes.

Femiotics also illuminates historical works, like Francisco Goya’s Witches’ Sabbath (1798), where witches gather in a carnivalesque ritual, their unruly bodies defying patriarchal order. These figures, with their abjected magic, mirror the subversive power of menstrual blood, showing how art has long wrestled with women’s uncontained embodiment.

Looking Forward

Join me over the next year for monthly posts diving into the thinkers who shape Femiotics—from Kristeva’s abjection to Federici’s witches as feminist rebels. This series will unpack their ideas, connecting theory to art. Together, we’ll explore how these voices illuminate female embodiment.

As I continue to develop the concept of Femiotics through my research and writing, I remain committed to its pluralistic potential. There is no single correct way to interpret the signs of female embodiment in art. What matters is creating a framework flexible enough to honour diverse expressions while precise enough to highlight their shared power.

In future issues of Embodied Visions, we'll explore how Femiotics applies to different artistic mediums, cultural contexts, and embodied experiences beyond menstruation. I invite readers to consider how this framework might illuminate art that you encounter, whether in galleries, museums, or online spaces. Next time you view works depicting women's bodies, ask yourself:

What Femiotic signs are being communicated?

How does the artist transform physiological processes into visual language?

Does the work contain, celebrate, or subvert traditional notions of the female body?

I welcome your thoughts on this emerging framework. Are there artists whose work you believe would benefit from a Femiotic reading? Are there dimensions of embodied experience that should be incorporated into this analytical approach? As Femiotics develops from concept to methodology, your insights will help shape its evolution.

This article introduces concepts that will be further developed in my forthcoming academic publication. The terms “Femiotic” and "Femiotics" represent original research emerging from my master's thesis ", Visualising Menstruation: Gendered Blood in Contemporary Art" (University of Auckland, 2014).

Image Credits:

Chen Lingyang, ‘March Peach Blossom’, 1999-2000, From the series Twelve Flower Months, Colour photograph, M+ Sigg Collection, M+, Museum for Visual Culture, Hong Kong.

Chen Lingyang, ‘November Camellia’, 1999-2000, From the series Twelve Flower Months, Colour photograph, M+ Sigg Collection, M+, Museum for Visual Culture, Hong Kong.

Chen Lingyang, ‘January Narcissus’, 1999-2000, From the series Twelve Flower Months, Colour photograph, M+ Sigg Collection, M+, Museum for Visual Culture, Hong Kong.

Shigeko Kubota, 'Vagina Painting', 1965 Fluxus Performance, Perpetual Fluxus Festival, 4th July 1965, NY.

Remedios Varo, ‘Encuentro (Encounter)’ 1959, oil on canvas, National Galleries of Scotland.

Francisco de Goya, ‘Witches’ Sabbath (El Aquelarre)’, 1797–1798, oil on canvas, 43 × 30 cm, Museo Lázaro Galdiano, Madrid, Image: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.