☽ Uncontained Power: witchcraft as embodied resistance across art history

from renaissance woodcuts to post-colonial film: seven visions of the witch

In this third edition of Embodied Visions, we explore the rich and complex history of witchcraft imagery in art, weaving together historical representations and contemporary reclamations through the lens of Femiotics—a framework for decoding signs of female embodiment in visual culture.

From Persecution to Power: Witchcraft as Femiotic Sign

The figure of the witch persists as one of the most enduring and complex symbols of female power in visual culture. Unlike the leaky body with its material fluidity—menstrual blood flowing, breast milk nourishing—the witch embodies a different kind of female transgressiveness: uncontained knowledge, spiritual autonomy, and subversive ritual. These elements make the witch a perfect subject for Femiotic analysis, which examines signs of female embodiment through material, symbolic, and performative dimensions.

As Barbara Creed observes in her pivotal work on the monstrous-feminine,

“It is her deviant femininity which is horrifying, not some hidden male aspect within her.”1

The witch terrifies precisely because she operates beyond the boundaries of proper womanhood, wielding power that escapes patriarchal containment. Her body becomes a site where material reality (herbs, potions, cauldrons) meets symbolic transformation (flight, shapeshifting, divination) through performative ritual (spellcasting, dancing, convening). From a Femiotic perspective, the witch represents a powerful nexus of material practice, symbolic transgression, and performative resistance.

Let’s trace this complex figure through centuries of visual art, examining how the witch evolves from object of fear to the subject of feminist reclamation using a Femoitic analysis.

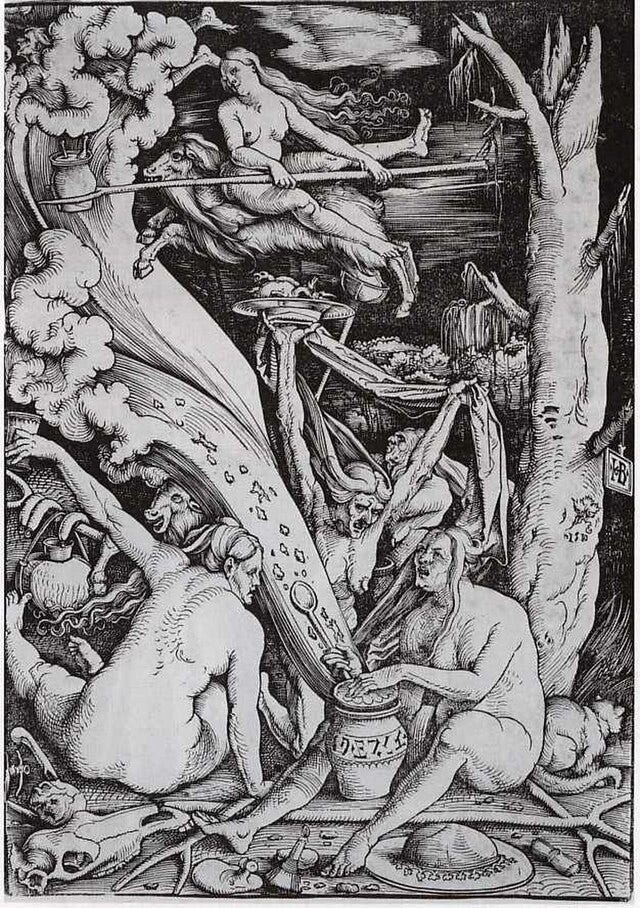

The Material Monstrosity: Hans Baldung Grien’s “Witches' Sabbath” (1510)

Baldung Grien’s chiaroscuro woodcut Witches Sabbath (1510) presents us with a nightmarish scene: nude women gathered in ritual, their bodies simultaneously voluptuous and grotesque. Visceral in its materiality, this Renaissance work exemplifies what Georges Bataille would later term the informe—the formless quality that disrupts categories and hierarchies.

On the material level, the medium itself speaks to the embodied nature of witchcraft. The artist’s knife gouges into wood, creating lines that flow and undulate across the surface. The rough-hewn texture of the print echoes the raw, earthy associations of witchcraft—roots, herbs, animal parts, and bodily fluids combined in cauldrons. The stark contrast between black ink and paper creates a sense of theatrical illumination, as if we're glimpsing forbidden knowledge by moonlight.

Symbolically, the work encapsulates the Renaissance fear of female collectives operating beyond male supervision. Their cauldron, brooms, and unbound hair function as Femiotic symbols of domestic tools repurposed for supernatural aims—the everyday made uncanny through feminine subversion. The women's naked bodies, far from the idealised nudes of classical art, are depicted with sagging breasts and distorted features—a visualisation of the monstrous-feminine that Creed would later theorise.

Performatively, Baldung Grien's impression enacted patriarchal anxiety through its public distribution. As a reproducible medium, the print disseminated images of “dangerous” female gatherings to a broad audience, functioning as both warning and entertainment. In Judith Butler's terms, it performed gender norms by visualising their violation, reinforcing proper femininity through depiction of its opposite.

This early visualisation establishes fundamental Femiotic codes that have persisted in witch imagery for centuries: the nocturnal gathering, the naked female body, the broom as vehicle, and the cauldron as transformative site.

Sensuous Subversion: Francisco Goya's “Witches’ Flight” (1798)

Nearly three centuries after Baldung Grien, Goya's Witches’ Flight (1798) presents a dramatically different materiality. The sensuousness of oil paint creates a more atmospheric rendering of witchcraft, with turbulent brushstrokes and dramatic chiaroscuro evoking the disorienting experience of supernatural flight.

Materially, Goya embraces what Elizabeth Grosz calls the “uncontrollable excess”2 of the witch's body. The painting's fluid brushwork and murky depths create a visceral sensation of bodies in motion, defying gravity and rational containment. The witches’ bodies are substantial yet weightless, occupying a liminal space between material flesh and ethereal spirit—embodying the Femiotic tension between corporeal presence and transcendent power.

Symbolically, Goya’s witches align with Mikhail Bakhtin’s concept of the carnivalesque. Their airborne bodies overturn the natural order, hovering above a landscape where a figure cowers below. This inversion of hierarchy—women above, man below—creates a symbolic disruption that challenges established power structures. As I explored in my thesis on gendered blood, Bakhtin’s concept of the carnivalesque body offers a powerful framework for understanding witchcraft imagery.

Bakhtin describes this body as one that ‘is not separated from the world... It is unfinished, outgrows itself, transgresses its own limits’3 Goya's witches embody this transgressive potential, their bodies escaping terrestrial boundaries.

Performatively, Goya’s painting Witches’ Flight functioned within Enlightenment scepticism toward superstition. Created for the Duke and Duchess of Osuna’s country home, the painting performed a complex social role—simultaneously acknowledging folk beliefs while allowing educated viewers to regard such beliefs with sophisticated distance. This performative context aligns with Michel Foucault’s concept of heterotopia—the painting creates a space of otherness within elite society, where forbidden knowledge can be safely contained within aesthetic contemplation.

Unlike Baldung Grien’s didactic horror, Goya’s Femiotic interpretation suggests a more ambiguous relationship between viewer and subject. Their suspended flight creates an unsettling beauty that both repels and attracts,4 suggesting the beginnings of a shift in how witchcraft imagery functions in art and visual culture.

Nineteenth Century Thresholds: Antoine Wiertz’s “The Young Sorceress” (1857)

As the nineteenth century progressed, the visual language of witchcraft evolved through the vision of Belgian Romantic painter Antoine Wiertz. His monumental The Young Sorceress (1857) captures a liminal moment in the transformation of witch imagery—bridging Goya's atmospheric ambiguity and the more explicitly psychological renderings that would emerge in the century to follow.

At the material level, Wiertz’s oil painting manifests the boundary-transgressing nature of the witch's body. Unlike Baldung Grien’s stark impression or Goya’s dreamlike atmospherics, Wiertz renders his subject with visceral immediacy—the sorceress’s nude form straddling her broomstick with unsettling intimacy. The painting’s substantial scale (220 × 135 cm) creates an overwhelming physical presence, while its dramatic light and shadow (influenced by Wiertz’s reverence for Rubens and Michelangelo) carves the witch’s form from darkness with almost sculptural dimensionality. This material emphasis connects to witchcraft’s corporeal nature, grounding supernatural power in flesh rather than fantasy—a key aspect of Femiotic analysis.

The shadowy, undefined background creates Bataille's notion of the informe—that unstructured space where boundaries dissolve and categories become unstable. The contrast between the sorceress’s illuminated flesh and the murky void surrounding her evokes the threshold space that witches traditionally inhabit: between visibility and invisibility, presence and absence, the material world and the supernatural realm.

Symbolically, Wiertz’s young sorceress represents a profound shift in the witch’s cultural meaning. Unlike the aged crones of Renaissance imagery, this witch appears in the prime of youth—her power explicitly connected to her sexual maturity rather than to post-menopausal wisdom or decline. Wiertz heightens this contrast by including a withered hag-witch lurking in the shadows behind the nude protagonist, creating a visual dialogue between traditional witch iconography and his more transgressive portrayal. This juxtaposition connects to Creed's analysis of the monstrous-feminine, where female sexuality itself becomes the source of cultural disquiet.

The broomstick—traditionally a symbol of domestic labour transformed for magical purpose—becomes in Wiertz’s rendering an unmistakably erotic implement, emphasising the connection between feminine sexuality and forbidden power that patriarchal systems found most threatening.

Performatively, the painting’s exhibition history creates multiple layers of subversion. Wiertz, that eccentric figure who rejected the commercial art market and secured state funding for his personal museum, displayed The Young Sorceress in his purpose-built Brussels studio (now Le Musée Wiertz). This deliberate institutional framing performed Butler's concept of ‘subversive reiteration’ of gender norms, placing the witch’s transgressive sexuality within a legitimate artistic space. For Victorian-era visitors, encountering this monumental nude witch in a museum setting created a heterotopia—a real place where multiple incompatible sites (the domestic, the erotic, the supernatural, the artistic) converge.

The Young Sorceress reimagines the witch and her broom as emblems of female embodiment, their material tactility, symbolic subversion, and performative defiance challenging patriarchal constraints. This Femiotic reading reveals how the witch figure evolves from pure horror to complex sexual power.

What distinguishes Wiertz’s witch from her predecessors is her ambiguous psychological presence. Neither fleeing persecutors (like Baldung Grien’s witches) nor participating in collective ritual (like Goya’s), she exists in communion with her own generative power. This introspective quality anticipates the twentieth century’s increasing interest in witchcraft as psychological rather than theological transgression. This shift would eventually enable feminist reclamations like those we are about to see in Ana Mendieta and Kiki Smith.

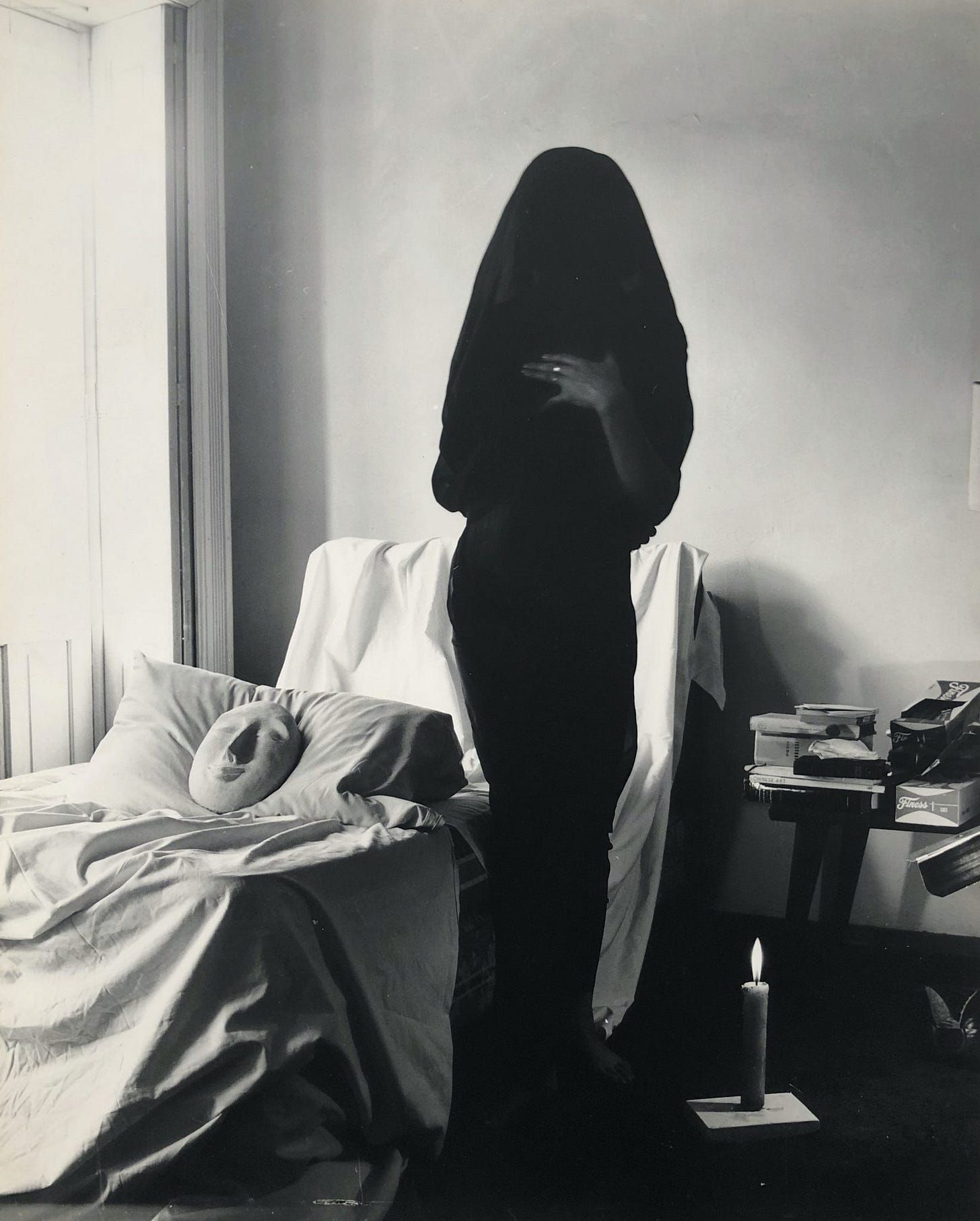

Surrealist Necromancy: Kati Horna’s “Untitled from Ode to Necrophilia” (1962)

With Hungarian-Mexican photographer Kati Horna’s surrealist work, we encounter a profound mid-century reimagining of the witch figure through the lens of avant-garde photography. This silver gelatin print from her series Ode to Necrophilia—published in the Mexican literary magazine S.nob in 1962—features British-Mexican surrealist painter Leonora Carrington engaged in a ritualistic tableau that evokes witchcraft’s (taboo) necromantic dimensions.

On the material level, Horna’s photograph creates a sensuous interplay of textures that embody Bataille’s informe—the destabilising quality that disrupts established categories. Carrington appears veiled in a delicate lace mantilla, a traditional mourning garment, as she stands beside a white plaster death mask resting on a pillow. The stark contrast between the mantilla’s delicate black fabric, the mask's smooth white surface, and the candle’s flickering light creates a tactile richness that connects to witchcraft’s material practices—the preparation of herbs, bones, and ritual objects. The half-open door allowing sunlight to spill into the otherwise shadowy room evokes Foucault’s heterotopia—a space where multiple realities converge, much like a witch’s liminal domain between the worlds of the living and the dead.

Symbolically, the photograph reimagines Creed's monstrous-feminine through a surrealist lens. Carrington, herself an artist whose paintings frequently depicted occult and alchemical imagery, performs a necromantic ritual that inverts patriarchal notions of proper female behaviour. Rather than fearing death or mourning passively, she appears to commune with it deliberately, evoking the witch’s traditional role as mediator between life and death. The plaster mask becomes what Irigaray terms a sign within her female imaginary—not a grotesque warning about mortality, but an object of power and knowledge within feminine ritual.

As Susan Aberth notes in her book on Carrington’s work, the artist was deeply invested in magical practices, viewing them as “autonomous expressions of female power.”5

Performatively, Horna’s photograph enacted a double subversion. First, through its publication in S.nob, it brought witchcraft-adjacent imagery into Mexico City’s intellectual and artistic circles during the conservative 1960s. Second, through its later exhibition in prestigious institutions like Tate Modern, it performed what Butler defines as a ‘parodic proliferation’ of gender possibilities, transforming a once-frightening female stereotype into an enigmatic celebration of feminine mystery. The photograph’s deliberate staging—with Carrington as performer and Horna as documenter—creates a collaborative feminine ritual that reclaims the power of the gaze from its historically masculine ownership.

What distinguishes Horna’s Femiotic contribution from earlier witch imagery is its surrealist refusal of simple categorisation. Neither condemning witchcraft as diabolical (like Baldung Grien) nor romanticising it as exotic (like Goya), it presents the witch-like figure as an intellectual, artistic force engaged in meaningful ritual. This resonates with Hélène Cixous's concept of écriture féminine—writing the feminine body into existence through creative expression—translating the photograph into a visual register where the witch emerges as artist, not merely as supernatural other.

Earthbound Ritual: Ana Mendieta’s “Untitled (Silueta Series, Mexico)” (1976)

With Ana Mendieta’s earthworks, we enter the contemporary feminist reclamation of witch-like ritual practices. Her Silueta Series (1976), where she imprinted her body in natural landscapes using elements like flowers, earth, fire, and blood, evokes ancient female earth-magic while situating it within contemporary art discourse.

Materially, Mendieta’s work embraces what Iris Marion Young describes as “lived feminine embodiment,”6 where the female body actively shapes and is shaped by its spatial surroundings. Mendieta creates direct corporeal engagement with natural elements by pressing her body into soil, arranging flowers in her silhouette, or igniting gunpowder traces of her form. This material immediacy recalls traditional witchcraft’s intimate relationship with natural substances—herbs, soil, bone, blood—while eschewing manufactured tools or technologies. As Mendieta explained,

“I have been carrying on a dialogue between the landscape and the female body. I believe this has been a direct result of my having been torn from my homeland during my adolescence. I am overwhelmed by the feeling of having been cast from the womb (nature).”7

Symbolically, Mendieta’s earth-body works evoke Irigaray’s concept of a ‘feminine cosmic imagery’—reconnecting women’s bodies with natural cycles and elemental forces. The artist’s Cuban-American identity adds layers to this symbolism, connecting her body-earth rituals to Santería traditions where feminine deities manifest through natural elements. The silhouette form creates a void within the landscape—simultaneously present and absent—symbolising the historical erasure of women’s magical practices while asserting their continued possibility. This Femiotic reading reveals how the witch's power becomes embedded in the earth itself rather than projected onto supernatural realms.

Performatively, Mendieta's private rituals, documented through photography, enact Butler’s notion of ‘subversive repetition of hegemonic forms’. By performing witch-like rituals within the legitimised context of performance art, Mendieta reclaims forbidden feminine power while critiquing both patriarchal art systems and colonial suppression of indigenous spiritual practices. The camera’s documentation creates a Foucauldian heterotopic space—a real location where multiple cultural spaces and times collide.

Mendieta’s witch-body becomes earth-bound in multiple senses—connected to soil, committed to terrestrial existence, and travelling toward culturally specific traditions rather than flying away into generalised fantasy.

Metamorphic Power: Kiki Smith's “Rapture” (2001)

With Kiki Smith’s monumental bronze sculpture, we encounter the witch as a figure of metamorphic transformation. Rapture (2001) depicts a woman emerging from a wolf’s body, her naked body strong—visualising the witch's shapeshifting power while referencing fairy tales, religious iconography, and feminist mythology.

Materially, Smith’s choice of bronze—one of the most ancient and durable artistic media, connects contemporary feminist art to archaic goddess traditions. The sculpture’s substantial weight and permanence contrast with historical depictions of witches as ephemeral or spectral beings. Every surface detail, from the wolf's textured fur to the woman's smooth skin, is rendered with tactile precision that invites haptic engagement. This material presence embodies what Grosz calls attention to as the body’s “materiality that is neither reducible to nature nor to culture.”

Symbolically, Smith's woman-wolf hybrid engages Creed’s monstrous-feminine while transforming it from object of horror to subject of power. The figure rising from animal form suggests not demonic possession but voluntary transformation—the witch who chooses to move between human and animal realms rather than being cursed or contaminated. As Smith has noted,

“I think a lot about metamorphosis... In fairy tales, people are endlessly transforming back and forth.” 8

This voluntary transformation symbolises women’s capacity to transcend culturally imposed limitations through reclaiming mythical connections to the animal world—a powerful Femiotic statement about feminine agency.

Performatively, Rapture functions within museum and gallery spaces as a contemporary art object that simultaneously references religious ecstasy, fairy tales, and feminist spirituality. Its public exhibition manifests Butler’s theory of ‘parodic proliferation’ of gender possibilities, expanding feminine embodiment beyond biological determinism or social constraint. The sculpture performs witch-power through its cultural hybridity—mingling Red Riding Hood with St. Teresa's ecstasy, Bronze Age goddess figures with contemporary feminist concerns.

Post-Colonial Echos: Zarina Bhimji's “Waiting” (2007)

Watch the video here.The next artwork I discuss is Zarina Bhimji’s Waiting (2007), a 35mm film installation transferred to digital video, housed at Tate Modern, London. As I cannot provide a still due to copyright restrictions, you can watch the full video on Bhimji’s artist website using the above link.

To expand our Femiotic exploration beyond Western traditions, we turn to Ugandan-Indian artist Zarina Bhimji’s haunting film installation Waiting (2007). While not depicting a conventional witch figure, this work captures women engaged in almost ritualistic labour at a sisal factory in East Africa, evoking a shamanic presence that resonates powerfully with witch-like archetypes across cultural boundaries.

Materially, Bhimji’s film creates a tactile, almost hypnotic atmosphere through its sensuous documentation of sisal fibres, dust particles suspended in shafts of light, and the rhythmic movements of workers’ hands. The motes of fibre floating in sunbeams create an ethereal texture that recalls the notion of informe—a materiality that blurs boundaries between human and environment, industry and ritual. The film’s warm, golden light transforms the factory into a space reminiscent of alchemical workshops where women transform raw material into refined substance through embodied knowledge.

Symbolically, Bhimji’s Waiting invokes Irigaray’s concept of a female imaginary, here extended into decolonial contexts—a way of knowing that reclaims industrial labour as a form of persistent feminine power. The sisal factory becomes a heterotopic space in Foucault’s sense, where colonial history meets spiritual resistance through women’s embodied knowledge. The slow, methodical work performed by the women can be read as a form of spell-casting, transforming plant matter through repetitive gestures that blur the line between factory production and ritualistic practice. As Bhimji herself has noted;

“There is always a history you don’t see... I am interested in that emotion.”9

Performatively, the installation of Waiting in elite art spaces like the Tate Modern enacts Butler’s ‘subversive reiteration’—bringing marginalised female labour into privileged viewing contexts. The film’s glacial pacing forces viewers to enter a meditative, almost trance-like state that mirrors aspects of ritual participation. This performative dimension creates a space where women’s work, often dismissed as mundane, is elevated to the realm of sacred practice. The women, filmed with dignity and grace, embody a quiet resistance that aligns with Creed’s reimagining of the monstrous-feminine as a source of power rather than an object of fear.

What makes Bhimji’s work particularly significant for Femiotics is how it expands our understanding of witch-like figures beyond European and American contexts. The women of Waiting are not labelled as witches by their societies, yet their embodied knowledge and transformation of materials connect them to witch/magic traditions worldwide. Their collective, rhythmic presence challenges Western individualism, suggesting that magical female power can manifest through community and shared labour, not just individual transgression.

Through the Kaleidoscope: Femiotics and Witchcraft Imagery

This Femiotic journey through witch imagery reveals how female embodiment evolves from object of fear to subject of power, while maintaining certain consistent material, symbolic, and performative elements. From Baldung Grien’s woodcut horrors to Smith’s ecstatic transformation to Bhimji’s post-colonial reframing, witches and witch-like figures embody female power that exceeds patriarchal boundaries.

Materially, witch imagery moves from the rough-hewn impressions of Baldung Grien to Goya’s atmospheric oils, Wiertz’s visceral chiaroscuro, Horna’s silver gelatin prints, Mendieta's ephemeral earth-body works, Smith’s substantial bronze, and Bhimji’s ethereal film, each material practice reflecting changing conceptions of feminine embodiment and power. This progression reveals how women’s magical practices transform from substance-based (cauldrons, potions) to embodied knowledge (gestures, labour) across cultural and historical contexts.

Symbolically, the witch transforms from monstrous threat to mankind (Baldung Grien) to ambiguous dream-figure (Goya) to embodied sexual power (Wiertz) to surrealist necromancer (Horna) to earth-ritualist (Mendieta) to spiritual shapeshifter (Smith) to collective labour ritualist (Bhimji)—her symbolic resonance expanding from patriarchal nightmare to feminist possibility to post-colonial reclamation. This arc demonstrates Femiotics’ capacity to trace symbolic evolution across Western and non-Western traditions, revealing unexpected connections between European witchcraft, Latin American earth rituals, and East African industrial labour.

Performatively, these works shift from reinforcing gender norms through horror (Baldung Grien) to aristocratic entertainment (Goya) to psychological introspection (Wiertz) to avant-garde subversion (Horna) to ritualistic reclamation (Mendieta) to mythic celebration (Smith) to dignified resistance (Bhimji)—the social function of witch imagery evolving from boundary enforcement to boundary dissolution to global recontextualisation. This performative progression illustrates how Femiotics can decode the increasingly diverse social roles of witch imagery in contemporary art and visual culture.

The witch, perhaps more than any other female archetype, demonstrates the capacity of Femiotics to illuminate embodied knowledge across historical periods, artistic media, and cultural contexts. The witch persists as a figure who refuses containment—whether flying through night skies, straddling a broom in solitary power, communing with death, merging with earth, emerging from animal form, or transforming raw material through embodied labour. Her unruly body and mind continue to inspire artists seeking visual language for female power that exists beyond patriarchal permission, regardless of cultural background.

Bhimji’s contribution is particularly significant in expanding our understanding of witch-like figures beyond Euro-American frameworks. By recognising the resonances between European witchcraft traditions and non-Western forms of female magical practice, Femiotics reveals itself as a truly global framework capable of illuminating female power across diverse cultural contexts without flattening their unique histories and meanings.

In our next exploration, we’ll turn our attention back to the leaky body, examining how maternal fluids—breast milk, amniotic waters, and post-partum blood—create another rich territory for Femiotic analysis. Until then, I invite you to share your own encounters with witch imagery in art, literature, or personal practice in the comments below.

Embodied Visions explores women's sacred traditions, embodied wisdom, and mystical art history. Subscribe for monthly deep dives into the visual cultures of the sacred feminine.

Creed, B. (1993). The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. Routledge, p. 83.

Grosz, E. (1994). Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism. Indiana University Press, p. 194.

Bakhtin, M. (1984). Rabelais and His World (H. Iswolsky, Trans.). Indiana University Press, p. 26).

In future posts, I will unpack this idea of ‘inter-repulsion’, drawing on the work of French philosopher Gilles Deleuze (1925-1995).

Aberth, S. L. (2004). Leonora Carrington: Surrealism, Alchemy and Art. Lund Humphries.

Young, I. M. (1980). ‘Throwing like a girl: A phenomenology of feminine body comportment, motility, and spatiality’. Human Studies, 3(2), 137–156. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02331805

Mendieta, A. (1981). Artist statement. Quoted in Clearwater, B. (Ed.). (1993). Ana Mendieta: A Book of Works (p. 11). Miami: Grassfield Press.

Smith, K. (2001). Interview. Quoted in Rexer, L. (2002, April 7). ‘Fairy tales move to a darker, wilder part of the forest.’ The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2002/04/07/arts/art-architecture-fairy-tales-move-to-a-darker-wilder-part-of-the-forest.html.

Bhimji, Z. (2012). Artist interview. Quoted in Tate. (2019). 5 things that inspire Zarina Bhimji. Tate. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/zarina-bhimji-12839/5-things-inspire-zarina-bhimji